Lec 08: HTML, CSS, JS

1. The internet

1.1. What is the internet

The internet is the network of networks of computers communicating with one another, which provides the infrastructure to send 0s and 1s. One the top of that foundation, we can build applications that send and receive data.

1.2. Routers

Routers are specialized computers, with CPU and memory, whose purpose is to relay data across cables or wireless technologies, between other devices on the internet, so that the data can be send far away ,like from China to USA.

1.3. Protocols

Protocols are a set of standard conventions, like a physical handshake, that the world has agree upon for computers to communicate with. E.g., there are certain patterns of 0s and 1s, or messages, a computer has to tell a router where it wants to send data.

1.4. TCP/IP

TCP/IP are two protocols for sending data between two computers. In the real world, we might write an address on an envelope in order to send a letter to someone, along with our own address for a letter in return.

The digital version of an envelope, or a message with from and to address, is called a packet.

IP stands for internet protocol, a protocol supported by modern computers' software, which includes a standard way for computers to address with each others. IP addresses are unique addresses for computers connected to the internet, such a packet sent from one computer for another will be passed along routers until reaches its destination.

- Routers have, in their memory, a table mapping IP addresses to cable each connected to other routers, so they know where to forward packets to. It turns out that there are protocols for routers for routers to communicate and figure out these paths as well.

DNS, domain name system, is another technology that translates domain names like www.google.com to IP addresses. DNS is generally provided as a service by the internet service provider, i.e. ISP.

Finally, TCP, transmission control protocol, is one final protocol that allows a single server, at the same IP address, to provide multiple services through the use of a port number, a small integer added to the IP address. E.g., HTTP, HTTPS, email, and even Zoom has their own port numbers for those programs to use to communicate over the network.

TCP also provides a mechanism for resending packets if a packet is somehow lost and not received. It turns out that, on the internet, there are multiple paths for a packet to be sent since there are lots of routers that are connected. So a web browser, making a request for a cat, might see its packet sent through one path of routers, and the responding server might see its response packets sent through another.

- A large amount of data, such as a picture, will be broken into smaller chunks so that the packets are all of a similar size. This way, routers along the internet can send everyone's packets more fairly and easily. Net neutrality refers to the idea that these pubic routers treat packets equally, as opposed to allowing packets from certain companies or of certain types to be prioritized.

- When there are multiple packets for a single response, TCP will also specify that each of them be labeled, as with “1 of 2” or “2 of 2”, so they can be combined or re-sent as needed.

With all of these technologies and protocols, we’re able to send data from one computer to another, and can abstract the internet away, to build applications on top.

2. Web development

2.1. What is Web development

The web is one application running one the top of the internet, allowing us to get web pages. Other applications like Zoom provide video conferencing, and email is another application as well.

2.2. HTTP

HTTP, or Hypertext Transfer Protocol, governs how web browsers and web servers communicate with TCP/IP packets.

Two commands supported by HTTP include GET and POST.

- GET allows a browser to ask for a page for a file

- POST allows a browser to send data to the server.

- POST doesn't include the form's data in the URL, but elsewhere in the request.

A URL, Uniform Resource Locator or web address, might look like https://www.example.com/

httpsis the protocol being used, and in this case HTTPS is the secure version of HTTP, ensuring that the contents of packets between the browser and server are encrypted.example.comis the domain name, where.comis the top-level domain, conventionally indicating the "type" of website, like commercial website for.com, or organization for.org. Now there are hundreds of top-level domains, and they vary in restrictions on who can use them, but many of them allow anyone to register for a domain.wwwis the hostname that, by convention, indicates to us that this is a “world wide web” service. It’s not required, so today many websites aren’t configured to include it.- Finally, the

/at the end is a request for the default file, likeindex.html, that the web server will respond with.

2.3. Requests and Responses

An HTTP request will start with:

- The

GETindicates that the request is for some file, and/indicates the default file. A request could be more specific, and start withGET /index.html. - There are different versions of the HTTP protocol, so

HTTP/1.1indicates that the browser is using version 1.1. Host: www.example.comindicates that the request is forwww.example.com, since the same web server might be hosting multiple websites and domains.

An HTTP can include inputs to servers, like the strings q=cats after ?:

A response will start with:

- The web server will respond with the version of HTTP, followed by a status code, which is

200 OKhere, indicating that the request was valid. - Then, the web server indicates the type of content in its response, which might be text, image, or other format.

- Finally, the rest of the packet or packets will include the content.

2.4. Status codes

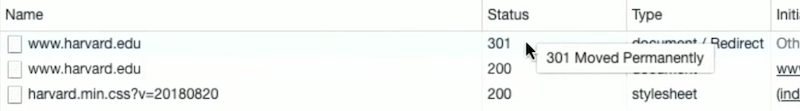

We can see a redirect in a browser by typing in a URL, like http://www.harvard.edu, and looking at the address bar after the page has loaded, which will show https://www.harvard.edu. Browsers include developer tools, which allow us to see what’s happening. In Chrome’s menu, for example, we can go to View > Developer > Developer Tools, which will open a panel on the screen. In the Network tab, we can see that there were many requests, for text, images, and other pieces of data that were downloaded separately for the single web pages.

The first request actually returned a status code of 301 Moved Permanently, redirecting our browser from http://... to https://...:

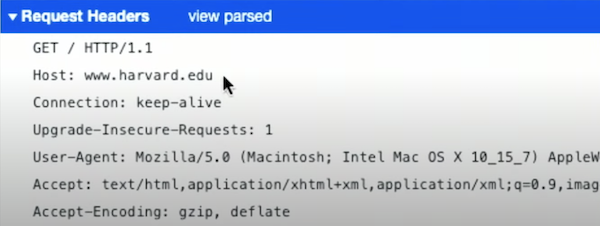

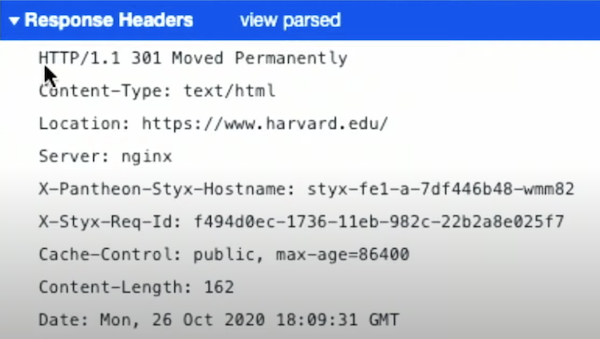

The request and response also includes a number of headers, or additional data:

- Note that the response includes a

Location:header for the browser to redirect us to.

Other HTTP status codes include:

200 OK301 Moved Permanently304 Not Modified- This allows the browser to use its cache, or local copy, of some resource like an image, instead of having the server send it back again.

307 Temporary Redirect401 Unauthorized403 Forbidden404 Not Found418 I'm a Teapot500 Internal Server Error- Buggy code on a server might result in this status code.

503 Service Unavailable- …

3. Contents for web pages

3.1. HTML

Since we can use the internet and HTTP to send and receive messages, now we can see what's in the content for web pages.

It turns out that HTML, Hypertext Markup Language, is not a programming language, but rather used to format web pages and tell the browser how to display pages, using tags and attributes.

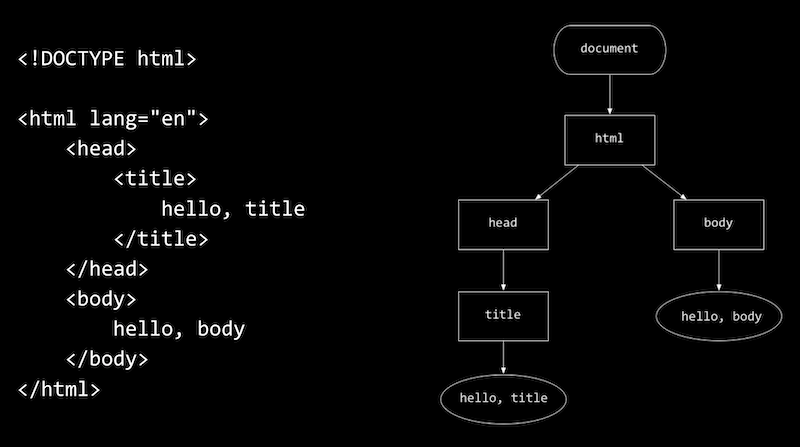

A simple page in HTML might look like this:

The page above will be loaded into the browser as a data structure, like this tree:

Each of HTML tags have two child tags, head and body.

Notice that rectangular nodes are tags, while oval ones are text.

There are other tags for other usages:

<p>, for a paragraph<h[1-6]>, for headings<ul>, for an unordered list<ol>, for an ordered list with numbers<table>, for table<tr>as rows<td>for individual cells, which stand for table data<img alt=? src=?>,imgtag for imagesaltattribute for alternative text for accessibilitysrcattribute for the source file of this image<a href=?>text<\a>,atag for an anchor, we can use it for hyperlink.hrefattribute is for a hypertext reference- Within the tag is the text that should appear as the link

- We could prank users with this, so the users will be tricked into visiting a fake version of some website.

- Phishing is an act of tricking users, a form of social engineering that includes misleading links.

By looking for documentation or other online resources, we can learn the tags that exist in HTML, and how to use them.

There is an example we can create a more complex form that takes user input and sends it to Google's search engine.

- First, we have a

<form>tag that has anactionof Google’s search URL, with a method of GET. - Inside the form, we have one

<input>, with the nameq, and another<input>with the type ofsubmit. When the second input, a button, is clicked, the form will append the text in the first input to the action URL, ending it withsearch?q=....

3.2. CSS

3.2.1. What is CSS

CSS, Cascading Style Sheets, which we can improve the aesthetics of our pages with, it's another language that tells our browser how to display tags of HTML on the page.

CSS uses properties, or key-value pairs, like color: red; to tags with selectors.

3.2.2. Including CSS in HTML

In order to include CSS in HTML, we have some options:

- We can add a

<style>tag within the<header>tag directly, and put CSS codes inside. - Or we can link to an external CSS file with a

<link>tag within the<head>tag. - We can also include CSS directly in each tag we want.

3.2.3. Include CSS directly in each tag

And notice that <header> , <main> and <footer> tags are like <p> tags, indicating the sections that our text on our page are in. For each of those tags, we can add a style attribute, with the value being a list of CSS key-value properties, separated by semicolons. Here we're setting the font-size for each tag and aligning the text in the center.

Note that ©, which is an HTML entity, as a code to include some symbol in our web page we cannot type it through our keyboard.

We can align all the text at once through apply the style attribute to <body> tag.

Here, the style applied to the <body> tag cascades, or applies, to its children, so call the sections inside will have centered text as well.

3.2.4. Separate our CSS from HTML and CSS type selectors

To factor out, or separate our CSS from HTML, we can include style in the <head> tag.

For each type of tag, we've used a CSS type selector to style it.

We can use a more specific class selector:

We've define our own CSS class with a . followed by a keyword we choose, each of those class have some property for font size or aligning.

Therefore we could reuse these classes by adding them to the attribute of our HTML tags, and it can have one or more classes for one tag.

3.2.5. Link an external CSS file

Finally, we can take all of the CSS for the properties and move them to another file with the <link> tag, rel for the relation.

3.2.6. More properties and selectors

With CSS, we'll also rely on references and other resources to look up how to use properties as we need them.

We can use pseudoselectors, which selects certain states:

Here, we're using a: hover to set properties on <a> tags when the users hovers over them.

We also have an id attribute on each <a> tag, to set different colors on each with ID selectors that start with a # in CSS.

3.3. JavaScript

3.3.1. What is JavaScript

To write code we can run in users' browsers, or on the client, we'll use a new language, JavaScript.

The syntax of JavaScript is similar to that of C for basic constructs, except for variable declaration:

We use the keyword let to declare any variable, instead of the type of this variable. That is because JavaScript is a loosely typed language same as Python.

With JavaScript, we can change HTML in the browser in real-time. We can use <script> tags to include our code directly, or from a .js file just like CSS.

3.3.2. JavaScript functions and DOM

We can create a greet function in JavaScript to interact with user.

We won't add a action to our form, since this will stay on the same page. Instead, we'll have an onsubmit attribute that will call a function we've defined in JS, and use return false; to prevent the form from actually being submit anywhere.

Since our input tag, or element, has an ID of name, we can use it in our script:

Where document is a global variable that comes with JavaScript in the browser, and querySelector is another function we can use to select a node in the DOM, Document Object Model, or the tree structure of the HTML page.

After we select the element with the ID name, we get the value inside the input, and add it to our alert. Notice that JS uses single quotes for strings by convention, though double quotes can be used as well as long as they match for each string.

We can also add more attributes to our form, to change placeholder text, change the button's text, disable autocomplete, or autofocus the input.

3.3.3. Listening events

We can also listen to events in JS, which occur when something happens on the page. For example, we can listen to the submit event on our form, and call the greet function when it's happened.

Notice in listen function we pass the function greet by name, and not call it yet. The event listener will call it for us when the event happens.

We need first to listen to the DOMContentLoaded event, since the browser reads our HTML file from top to bottom, and form wouldn't exist until it's read the entire file and loaded the content. So by listening to this event, and calling our listen function, we know form will exist.

We can also use anonymous function in JS:

We can pass in a lambda function with the function() syntax, so here we’ve passed in both listeners directly to addEventListener.

3.3.4. Other events

In addition to submit, there are many other events we can listen to:

blurchangeclickdragfocuskeyuploadmousedownmouseovermouseupsubmittouchmoveunload...

For example, we can listen to the keyup event, and change the DOM as soon as we release a key:

Notice that we can substitute strings in JS as in Python, with the ${input.value} inside a string surrounded by back-ticks, `.

3.3.5. Changing Style in JS

We can programmatically change style, too.

After selecting an element, we can use the style property to set values for CSS properties as well. Here, we have three buttons, each of which has an onclick listener that changes the background color of the <body> element.

Also notice that our <script> tag is at the end of our HTML file, so we don't need to listen to the DOMContentLoaded event, since the rest of the DOM will already have been read by the browser.

4. My first website

4.1. Planning

We'll think about three questions:

- What's our website about?

- Just a personal website, like a blog.

- What information do we presenting on the subject?

- Any informations about me, so that others could know me through my website.

- What does our website look like?

- More tech style, cool

4.2. File structure

Our folders and files should completely in lowercase with no space.

- Many computers, particularly web servers, are case-sensitive.

- Browsers, web servers, and programming languages do not handle spaces consistently.

Long story short, we should use a hyphen - for our file names, rather than underscore _, cause the Google search engine treats a hyphen as a word separator but does not regard an underscore that way.

Our file structure will contain an index HTML file and folders to contain images, style files, and script files.

index.html: This file will generally contain our homepage content.imagefolder: This folder will contain all the images that we use on our website.stylefolder: This folder will contain the CSS code used to style our content.scriptfolder: This folder will contain all the JavaScript code used to add interactive functionality to your site.